Eric and Wendy Schmidt to fund space telescope, three ground-based observatories

The Schmidts' philanthropic research organization will build a 3-meter space telescope and fund three ground-based facilities.

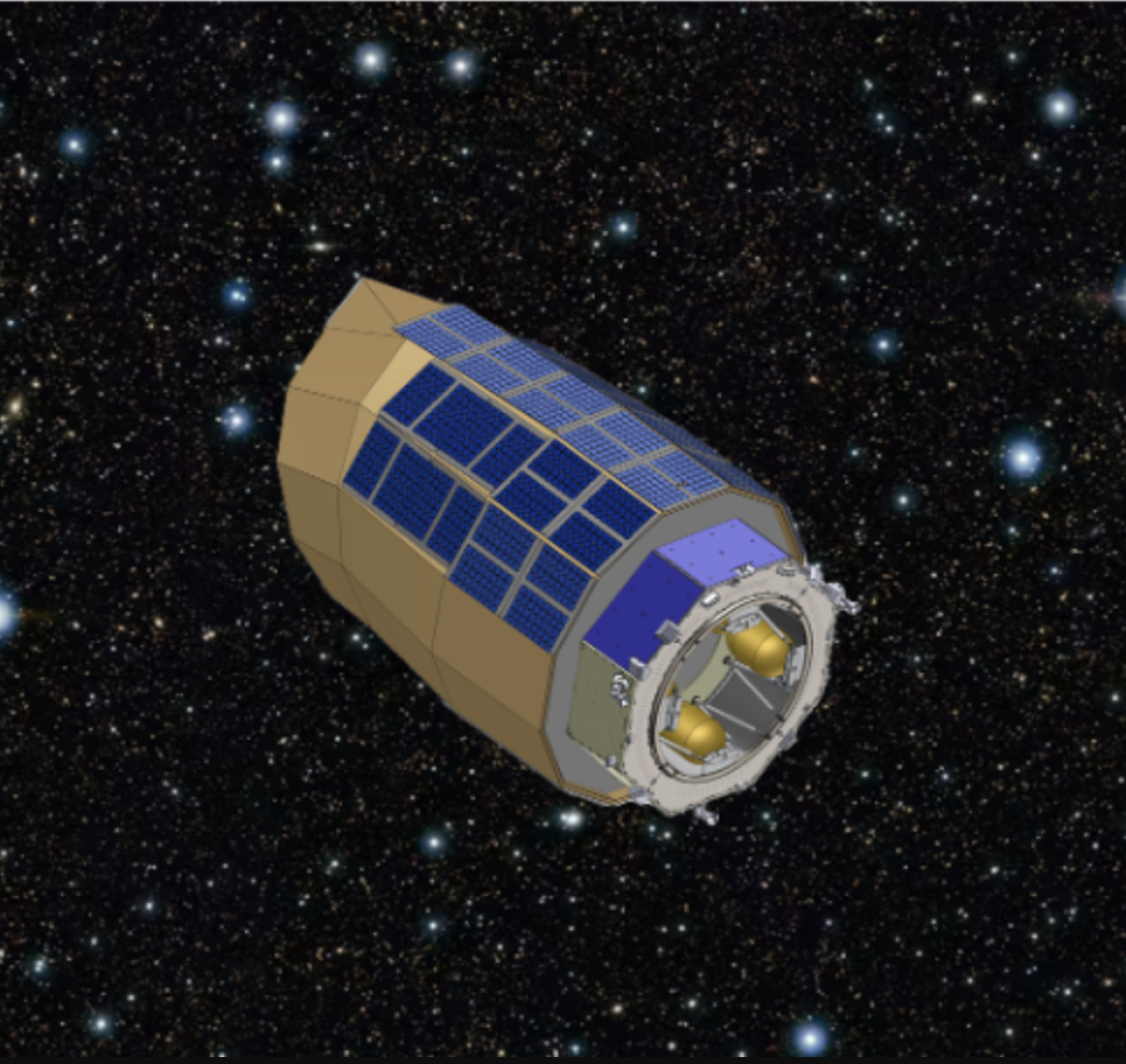

Lazuli will be the largest privately funded space telescope ever built — larger than the Hubble Space Telescope.

Schmidt Sciences

On Wednesday, Schmidt Sciences — an organization funded by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and his wife, Wendy Schmidt — announced an ambitious initiative to build a space telescope larger than Hubble and fund the construction of three innovative ground-based observatories.

Together, the four facilities are called the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Observatory System and cover optical imaging, spectroscopy, and radio astronomy. Officials say they are aiming to have all four facilities operational and doing science by 2029, and some even earlier. And once these facilities are built, they will consider building more.

The announcement came Wednesday in a jam-packed conference room at the annual winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), being held in Phoenix.

The initiative marks a major expansion of the Schmidts’ philanthropic efforts in astronomy through the Schmidt Sciences organization. The couple has previously funded the Schmidt Ocean Institute, run by Wendy Schmidt, which operates marine research vessels.

The new investment in astronomy is “a very large, purely charitable gift from Eric and Wendy Schmidt as basically a gift in new platforms and systems for the global astrophysical community,” said Stuart Feldman, the noted computer scientist and president of Schmidt Sciences, at the AAS session.

“For 20 years, Eric and I have pursued philanthropy to seek new frontiers, whether in the deep sea or in the profound connections that link people and our planet, committing our resources to novel research that reaches beyond what might be funded by governments or the private sector,” said Wendy Schmidt in a statement. “With the Schmidt Observatory System, we’re enabling multiple approaches to understanding the vast universe where we find ourselves stewards of a living planet.”

Wide-ranging capabilities

Philanthropy has long played a significant role in funding the construction of U.S. ground-based observatories from Mount Wilson to Keck, although the total amount of private investment is much less than public funding.

But a privately funded space telescope of this scale is unprecedented: The observatory, named Lazuli, will feature a 3-meter mirror and a powerful coronagraph — an instrument to block out the glare of stars, allowing the telescope to observe exoplanets. It will have instruments to both image those planets and study their atmospheres with spectra. It will also be designed to rapidly slew across the sky to catch cosmic explosions as they occur.

Lazuli’s capabilities will “approach Hubble” but “for a ridiculously low price,” said Pete Klupar, executive director of Schmidt Sciences, at the AAS session. Klupar is leading the engineering team building the Lazuli spacecraft. The mission was first proposed by a team led by Saul Perlmutter, the astrophysicist who shared the 2011 Nobel Prize for discovering the acceleration of the universe’s expansion. “He realized that we could build a groundbreaking mission for pennies” compared to NASA flagship observatories, said Klupar.

The telescope’s design and capabilities were publicly outlined for the first time in a paper that was posted to the arXiv preprint server on Tuesday. The authors wrote that its science portfolio will include studying supernovae, objects that generate gravitational waves, and cosmology.

Each of the ground-based facilities greenlit by the Schmidts are arrays with innovative designs — two of them optical and one radio — that were previously in development by existing teams at academic institutions.

The Argus Array, led by the University of North Carolina, will combine more than 1,000 small telescopes to form a telescope with roughly the collecting area of an 8-meter mirror, rivaling some of the largest ground-based observatories. The array will continuously observe the northern sky, making its mission something of a Northern Hemisphere complement to the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile.

However, it will have a very different operating strategy; instead of taking deep imagery that covers the sky every few days like Rubin, Argus will observe the entire sky continuously, making more of a real-time movie. Some regions of the sky will be imaged every second. It will generate up to 7.8 petabytes of data per night, which will be processed with graphics processing units (GPUs).

The array will quickly find light emitted by events that create gravitational waves, like mergers of neutron stars. It should be able to discover thousands of supernovae “within minutes of the explosion,” said Nicholas Law, the leader of the Argus Team, at the AAS meeting session.

Telescopes for this array have been in production by Observable Space since the summer of 2025. The Argus team expects to be on sky with the full array of telescopes in 2027, said Law. They have not yet announced the site location.

The Large Fiber Array Spectroscopic Telescope (LFAST) will be a large array of small telescopes, but one designed to enable spectroscopy of faint objects. This will let it search exoplanet atmospheres for biosignatures and studying supernovae in detail.

The array will use optical fibers to feed light from each mirror to a spectrograph. The mirrors will be organized in subarrays of twenty 30-inch telescopes on a single structure. Team leader Chad Bender of the University of Arizona said the number of the subarrays has not been determined, as the concept is meant to be scalable. He noted that one such structure has the collecting area of a 3-meter telescope, while 10 of them is equivalent to one of the 10-meter Keck observatories. But they are aiming for more — enough to have a collecting area equivalent to a 30-meter-class telescope. Bender said their preferred site is Kitt Peak, with Mount Lemmon and Mount Hopkins as backup sites.